SEPT-OCT 2018 – There’s been a lot of buzz lately about the benefits of biochar as a soil amendment. It’s been touted not only as a fertility enhancer but also for its potential to sequester carbon, reduce greenhouse gasses, suppress plant disease and remediate contaminated soil.

Biochar isn’t fertilizer but it has a porous structure that attracts beneficial micro-organisms and helps soil retain water and nutrients.

According to the U.S. Biochar Initiative (biochar-us.org), it’s a fine-grained charcoal made by pyrolysis, the process of heating biomass with limited to no oxygen in a specially designed furnace capturing all emissions, gases and oils for reuse as energy.

Depending on the temperature used, the process yields a varying mixture of biochar, bio-oil and syngas. Some sources recommend a minimum of 450°C for biochar. Temperatures of 700°C and higher favor the creation of biofuels.

What’s in Biochar?

In modern times, the biomass used to create biochar can be almost any type of organic waste including timber and forestry byproducts, yard litter, grasses, crop residues, and even invasive plants. This feedstock can vary with regional availability.

The final product is extremely porous and, as a result, has a large surface area. This means it’s very good at retaining water and soluble nutrients. Dr. Elaine Ingham, a soil biologist and founder of Soil Foodweb Inc (soilfoodweb.com) notes that it makes excellent habitat for beneficial soil micro-organisms.

Dr. Joseph Pignatello, head of the Dept. of Environmental Sciences at The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES) in New Haven, says “We discovered that biochar increases colonization of roots by beneficial mycorrhizal fungi. They form symbiotic relationships with plants, which improves growth.”

Todd Harrington of Harrington’s Organic Land Care in Bloomfield says “Due to the fact that good biochar doesn’t break down for hundreds of years, we find it makes a great home for microbes to colonize, grow, thrive, multiply, produce and cycle nutrients.”

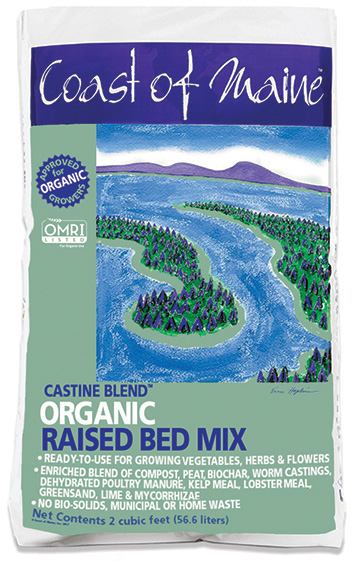

Cameron Bonsey at Coast of Maine says they’re now using biochar in their Castine Blend, an organic mix for raised beds. He considers biochar’s ability to capture and retain moisture and nutrients a key benefit.

“There is some very good char and some very bad char

– Todd Harrington, Harrington’s Organic Land Care

out there.”

What Are the Benefits of Using Biochar in the Garden?

The reported benefits are numerous and include:

• Increased crop yields

• Improved soil structure

• Increased nutrient retention

• Increased water retention

• Increased Cation Exchange Capacity

• Improved drought resistance

• Improved propagation results

• Suppression of plant root diseases

• Suppression of allelopathy

• Reduced greenhouse gas emissions

• Reduced need for fertilizer

• Resists decomposition

• Binds with and degrades pesticides

• Detoxifies heavy metals

• Sweetens soil

• Increases mycorrhizal activity

• Long-term carbon sequestration

• Improved micro-nutrient concentrations in produce

Keep in mind that more research is required to confirm some claims.

History

Biochar may sound like a new discovery but the basic idea is actually quite old. Charcoal, which is akin to biochar, has been discovered at many archeological sites of great antiquity.

In the 1540s, Francisco de Orellana, a Spanish explorer, searched for the lost city of gold (El Dorado). His adventures were chronicled by Gaspar de Carvajal, a Dominican friar.

Their improbable journey started in Ecuador on the Pacific Ocean. The party crossed the Andes, descended into the Amazon River Basin and may have been the first foreigners to navigate the length of the Amazon River.

Along the way they reported seeing an advanced civilization associated with large structures, roads, and patches of black, fertile earth. The accounts have routinely been dismissed as fanciful fundraising propaganda because it’s generally assumed that the region’s infertile, acidic soils were incapable of supporting a large civilization.

Orellano’s sightings of an advanced Amazonian civilization have beenchallenged but the dark earth he mentioned was rediscovered, centuries later, by a number of explorers and researchers in the late 1800s.

Terra Preta

Called terra preta (dark earth), the deposits were composed of charcoal-like material (perhaps from forest burns, kilns or cooking fires), charred plant material, kitchen refuse, fish and animal bones, manure, potsherds, and the decomposed biomass of terrestrial and aquatic plants.

Although it’s difficult to prove, many now believe the indigenous people were actively enhancing their infertile native soil thousands of years ago.

According to Organic Gardening, “Indigenous people didn’t practice slash-and-burn farming as they do now. They practiced slash-and-char agriculture, roasting wood and leafy greens in ‘smothered’ fires, in which lower temperatures and oxygen levels resulted in the production of charcoal instead of ash. The charcoal was buried in fields where crops were grown.”

In the present day, locals still search out terra preta for use as compost starter or potting soil.

Magic Soil of the Ancients?

Terra preta is very fertile and maintains that fertility, says Johannes Lehmann, a professor at Cornell University and a leading authority on biochar.

The enduring fertility of terra preta, its ability to persist and regenerate, fascinates scientists … for good reason.

How did an ancient civilization, overlooked by many, come up with something so unique and effective? Even with all of our scientific and technical advances, we still don’t fully understand all of the processes involved.

Caveat Emptor

Like cookbook recipes, procedures and ingredients for creating biochar vary. This could be a good thing. Different materials and proportions can be pyrolyzed at different temperatures and durations to create different products for specific uses. The amount of oxygen allowed, and the timing of its introduction, also appears to be an important variable. Some of these factors can also impact the longevity of the product.

Keep in mind that some manufacturers may be adding things to their biochar (such as fertilizer) to make it seem better to the consumer.

Biochar can be expensive so you want to be sure you know what you’re getting and use it properly. Mark Highland at Organic Mechanics recommends going for 5% biochar by volume.

“There is some very good char and some very bad char out there,” says Harrington. “The International Biochar Initiative (biocharinternational.org) has developed some good standards and guidelines for the companies that are producing and manufacturing the char so that it is of higher quality than what has been produced in the past.”

“Biochar still needs to be tested and validated for each region, soil type, and plant before issuing a blanket recommendation for its use,” says Pignatello.

Inoculation

Biochar intended for use by the home gardener is usually pre-inoculated with nutrients and biologics. Some do-it-yourselfers inoculate biochar by mixing it with their compost.

“Whether or not to use inoculated biochar depends on its purpose,” says Bob Wells of New England Biochar in Eastham, Mass. (newenglandbiochar.com) “My company does not generally sell biochar to the public without inoculating it first for the simple reason that, when added to the soil, biochar will actually tie up some of the available nutrients initially if it hasn’t been treated properly first.

“On the other hand, if our biochar is being used to remediate an area of soil that has been polluted with some toxic chemical or heavy metal pollution, or is going to be used in some form of filter then it should start out pure and clean, leaving it able to attach to as much of the toxin as possible.”

Is Charcoal Biochar?

Not really. Although charcoal is created in a manner similar to biochar, it may not, depending on the charcoal, be suitable as a soil amendment.

According to Dr. Pignatello, “Some charcoal you can buy at the supermarket or hardware store is made, not from wood products, but from coal powder pressed into briquette-size pieces before pyrolysis.”

Connecticut has a long history of charcoal manufacturing but charcoal from your campfire or firepit is probably preferable to store bought.

Biochar for the Home Gardener?

When I wrote the first draft of this story in 2016 biochar was not widely available. Recently we’ve seen it make its way into soil amendments intended for the home gardener.

“In home gardens biochar may allow for less fertilizer, better water uptake during periods of drought, and improved mycorrhizal relationships,” says Pignatello. “By altering the microbial composition in the soil toward a disease suppressive community, biochar could assist plants in providing a natural protection from pathogens, but further research is necessary before broad generalizations applicable to the home gardener can be made.”

Biochar has perhaps its greatest potential benefit in semi-arid regions and the tropics, such as rural Africa, where it may improve the capacity of soil to hold moisture. Marginal soils stand to benefit the most.

It’s also reputed to regulate the bioavailability of nutrients to plants and reduce nutrient leaching. However, these processes are complex and results can be inconsistent. Further research is needed to figure it all out.

“Due to its porous and active surface properties biochar has attracted attention as a potentially beneficial soil amendment in agriculture and environmental remediation,” says Pignatello. He and other scientists at CAES are collaborating with a number of institutions and looking at its potential from several different angles.

Some producers, such as Paul Sachs at North Country Organics in Vermont, have adopted a wait-and-see attitude. While recognizing the potential benefits of biochar, Sachs notes that it’s expensive and takes energy to produce. He’s also aware that terra preta wasn’t created in a day.

– Will Rowlands

MORE INFORMATION

Biochar: A Home Gardener’s Primer is a good summation from Linda Chalker-Scott, an associate professor at Washington State University. You can find it at cru.cahe.wsu.edu/CEPublications/FS147E/FS147E.pdf