By Charlie Stebbins

An “Arboretum” is an outdoor “tree museum,” open to the public and offering a verdant sanctuary of quiet and beauty. With forests worldwide threatened by development, invasive pests, diseases, and plants, plus poor management practices, the need for quality “arboreta” was never so pressing. Fortunately, the expanding community of tree-loving enthusiasts grows increasingly strong!

Arboreta have been around since Roman times and today they total about 4,000 globally. Botanical gardens feature herbaceous flowers and grasses, while trees and woody shrubs are the stars in an arboretum. Long ago, arboreta were simply “places of trees,” randomly arrayed in old cemeteries, universities or municipal parks. Documentation, landscape legacy, and history were seldom known. That said, some arboreta are time-honored horticultural landmarks, like London’s Kew Gardens or Boston’s Arnold Arboretum. Until recently, there were no standards or benchmarks to measure the impact and value of so many less-renowned “tree museums.”

That changed in April 2011 when The Morton Arboretum launched an international accreditation program called “ArbNet” which broke new ground to weave together the arboreal community. This program showcases arboreta while promoting tree specimen sharing, research collaboration and public outreach.

The Morton Arboretum may not be as well-known as Kew or Arnold, but Morton is an historic visionary. Founded a hundred years ago in 1922, the now 1,700-acre arboretum was established by Joy Sterling Morton, founder and millionaire entrepreneur of the Morton Salt Company. Trees and salt seem an unlikely pairing, but Joy loved trees, it was in his blood. Joy’s father was Julius Sterling Morton, creator of the first Arbor Day held April 10, 1872 in Nebraska City, Nebraska where a million trees were reportedly planted in a single day!

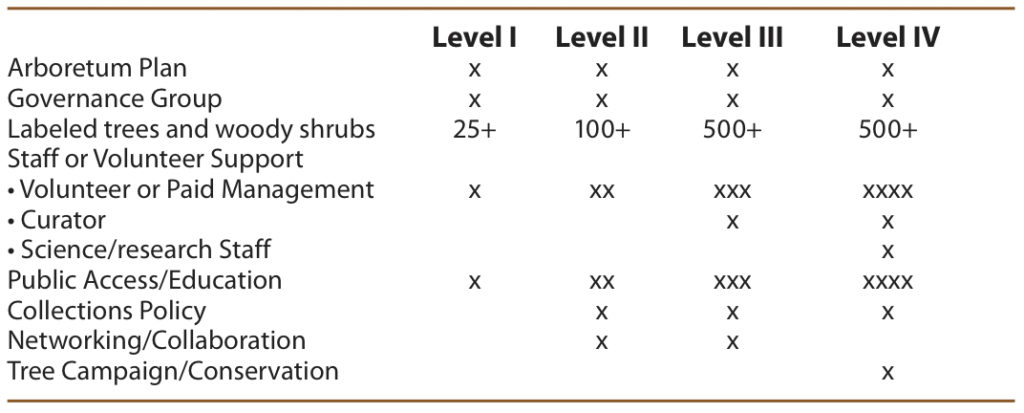

The present-day Morton Arboretum is impressive, nurturing 222,000 specimens, 4,650 plant “taxa” (different types of plants) just south of Chicago. However, Morton’s influence extends beyond its own extensive plant collection. When it rolled out ArbNet, Morton created a 4-Level scorecard that sets “industry standards for the purpose of unifying the arboretum community.”

ArbNet’s accreditation criteria challenges organizations to extend beyond merely taking care of trees, but inspires a worldwide community dedicated to preserving, teaching, researching, and celebrating the beauty of trees. Regardless of level status, this community networking is crucial. Since its rollout, ArbNet has registered over 2,300 arboreta, accredited 652 properties in 40 countries and registered over 4,000 “tree museums.” Be it parks, sanctuaries, graveyards or school yards, ArbNet has created an invaluable template to showcase and challenge the world’s “tree museums.”

Yet ArbNet standards are not easy and steepen quickly. Level I simply requires a handful of 25 different tree types, public access, and a general specimen growth plan. Not too daunting. However, the scorecard gets tougher for Level II, requiring a tree/shrub species count of at least 100, attainable for many, but tougher hurdles come next. At Levels III and IV, the tree/shrub threshold jumps to 500 species; add in a commitment to professional staffing (e.g., hiring a curator and/or botanist), conducting scientific research, possibly erecting green houses, and collaborating with other arboreta. Not inexpensive nor trivial. Of the 2,500 arboreta accredited worldwide, fewer than 5% are able to boast of either Level III

or IV status.

ArbNet’s Accreditation scorecard below illustrates the challenge:

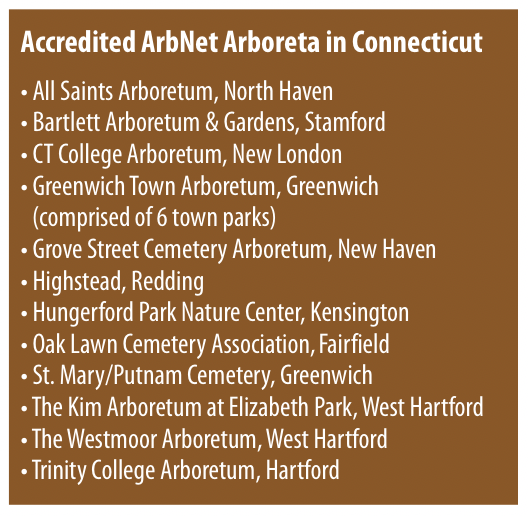

Here in Connecticut, we have 12 accredited arboreta, but only one above Level II, the Connecticut College Arboretum in New London at Level III. With its exceptional plant collection established in 1931, Connecticut College displays over 800 plant taxa, a nationally-accredited native azalea collection, and gorgeous naturalized landscapes and wetlands on the 750-acre campus arboretum. Director Maggie Redfern says they would like to achieve Level IV status, but need to expand their botanical research and broaden plant collecting and collaboration with fellow arboreta. While Connecticut College created the state’s first arboretum, Maggie says “Every arboretum is still an arboretum” and regardless of size or rank, each is valuable and special.

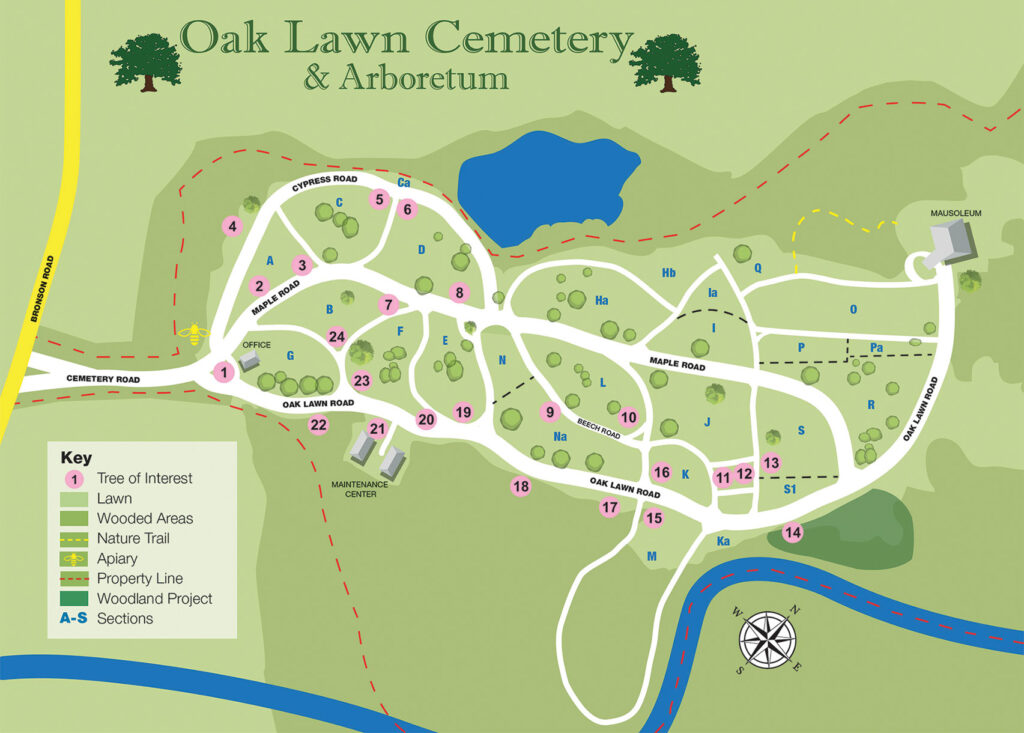

In 2014, the Connecticut College Arboretum and Fairfield’s Oak Lawn Cemetery and Arboretum became the state’s first accredited ArbNet properties. Oak Lawn rose to Level II in 2020, but Level III is a big jump, requiring not only 500 tree and shrub species (up from its 200 today), but necessitating a huge financial and staffing commitment. Such investments exceed the resources of many arboreta, but some are lucky enough to be located near a well-endowed university and the synergy can be compelling. Philadelphia’s Morris Arboretum & Gardens is a perfect example where the Morris family gifted its 175-acre spread to the University of Pennsylvania, and now the Morris “outdoor lab” is an important part of UPenn’s botanical graduate studies.

Oak Lawn also has a compelling history, but no grand benefactor. Founded in 1865, Oak Lawn is a classic rural cemetery. Though it cannot match the scientific and financial muscle of Morris, Kew or Arnold, Oak Lawn is dedicated to land conservation and preservation. Oak Lawn’s Board Chair Bronson Hawley embraces ArbNet’s vision “to collect trees, shrubs, and other woody plants for the benefit of the public, science, and conservation.” Oak Lawn adheres to a solid set of horticultural disciplines:

• Vision: Support Public Access, Science and Conservation

• Labeling: Tag species (75 tagged at Oak Lawn)

• Signage: Tell stories and educate

• Community: Engage through Audubon bird and plant walks

• Plant Collections: Document plant variety, age, and provenance

• GPS Mapping: Locate each specimen on its 100-acre property

• Acquisition strategy: Expand collection, special focus on oaks

• Property Management: Remove invasive plants and replace with native trees and woody shrubs

For Oak Lawn, conservation is in its DNA. One of Oak Lawn’s “permanent residents” is Mabel Osgood Wright, who founded The Connecticut Audubon Society in 1898. She was a forceful voice for wildlife, helping end the slaughter of birds for the “feather trade” through direct lobbying of President Theodore Roosevelt. As a cemetery board director, she led the transformation of the burial grounds into “Oak Lawn” inspired by the old “Cemetery Oak” flourishing at the cemetery’s Bronson Road entrance. Over the years, Oak Lawn has lived up to its name, nurturing 30 oak species and adding new varieties each year. Besides the usual assortment of white, pin and red oaks, their collection includes overcup, shingle, chinkapin, nuttall, sawtooth and its first southern “live oak” which was added just this month (thanks to global warming.) Renowned entomologist and horticulturalist Doug Tallamy declares native oaks the kings of the forest due to their incredible power to host over 500 species of delectable insects and caterpillars, vital food to breeding birds and their nestlings. Mabel picked the right tree to champion.

Jed Duguid, owner of Oliver Nurseries in Fairfield and Oak Lawn board director, was inspired a decade ago to elevate Oak Lawn Cemetery as an arboretum and found great support from fellow board members, most notably Dr. Bill Allen and arborist Don Parrott. Jed, Bill, Don and other board directors visited the storied Green-Wood and Woodlawn cemeteries in New York to learn from the best. Though less famous, but no less historic, the board felt Oak Lawn had the trees to highlight its own arboreal prowess.

With Directors Allen and Parrott leading the accreditation effort, Oak Lawn worked hard to achieve both Level I and II status. When Dr. Danica Doroski later joined the team, she brought her expertise on how to manage a proper arboretum. With horticultural and ecological experience from UPenn’s Morris Arboretum, Bates, and Yale, Danica is meticulously implementing best practices of plant documentation by creating detailed accessioning and inventory records. With nearly 200 trees and woody shrubs to catalog, the job is not easy as many old trees have no recorded histories. Still, each new specimen is now scrupulously “geo-located,” then logged with a date, origin and species type (straight/hybrid/cultivar). When dead, the specimen is “de-accessed” with notes describing its age and possible cause.

The Oak Lawn story is just one of many in Connecticut and the pipeline of new ArbNet candidates is growing. Connecticut has an enviable tableau of native flora, diverse hardwood and softwood forests. We Yankees grieve the loss of our white ash, elms, hemlock, and chestnuts … and lament our withering dogwoods, beech and sugar maples as well. But thank you hickories, walnuts, basswood, oak, cherry, aspen, and birch. All flourishing in our state. With climates warming, we also welcome newcomers from the South, namely yellowwood, large-leaf magnolia, bald cypress, Kentucky coffee trees … and Oak Lawn’s new live oak.

So, we thank the Morton Arboretum for creating ArbNet and challenging the world’s arboreta to strive for higher goals. May our “tree museums” inspire the next generation of conservationists and continue to provide us peaceful sanctuary for years to come.

Charlie Stebbins has morphed from a 35-year Morgan banker to a “native plantsman.” Charlie is on the Board of the Oak Lawn Cemetery & Arboretum, following seven years on the State Board of the Connecticut Audubon Society. He designs and leads native landscape and restoration projects for the Audubon, Aspetuck Land Trust, Oak Lawn, Pollinator Pathways and other public and private clients. Charlie is most proud of restoring Audubon’s Smith Richardson Wildlife Preserve in Westport. He is a frequent speaker and tour guide espousing the ethic of native landscaping and ecological land conservation.