By Richard Cowles

Overpopulation of white-tailed deer poses a difficult challenge to growing crops, gardens, and ornamental landscape shrubs. When there are too many deer and not enough mast (nuts, such as acorns from oaks, in particular) to sustain deer during the winter, they will browse on almost any plants.

During the summer, deer cause major losses as they eat favored plants such as soybean and tomato crops, and in the autumn, they destroy the commercial value of pumpkins and squash through their habit of taking a few bites out of each fruit.

Browsing damage to Christmas trees can destroy the aesthetic value of trees and set them back several years in growth (Fig. 1). Bucks marking territory through rubbing of antlers can destroy the bark on small trees.

Fig. 1 – Deer browse damage to Christmas trees sets them back several years from being marketable.

Several approaches can be useful for limiting deer populations, such as hunting and protection of deer predators, but lethal measures (guns, bears, and mountain lions) can also jeopardize human safety.

Excluding deer through fencing may be effective for very valuable crops, such as fruit orchards and ornamental plant nurseries, but are not usually practical in a suburban landscape.

Because there are so few other practical options for garden enthusiasts, changing the deer’s behavior to cause them to reject otherwise palatable foods by using repellents is one of the few options left.

Commercially available deer repellents may have active ingredients that (1) smell or taste like non-host plants, (2) smell like other animals, or (3) are toxic (e.g., thiram).

The first category includes essential oils from plants in the mint family (mint, thyme, or rosemary) or spicy substances (red or black pepper). One challenge in using volatile odorous ingredients is that, because they are volatile, they either evaporate too quickly to provide long-term benefits, or they can harm our plants when applied at a high enough concentration to obtain longer benefit. The same concern about volatility could apply to any compound odorous enough to be detected at a distance to repel deer.

In the second category, odors associated with human waste (Milorganite®), animal blood (PlantSkydd®), or putrescent egg solids (several products) can be effective for a short period, but then they degrade and wash off until they are no longer effective. One effective deer repellent is putrescent egg solids, and products containing this ingredient provide benefits for about five weeks (Curtis and Eshenaur 2022).

Drs. Paul Curtis and Brian Eshenaur, Cornell University specialist in natural resources and extension plant pathologist, respectively, tested the effectiveness of Trico deer repellent, manufactured by Kwizda Agro GmbH, an Austrian company, both in Christmas tree plantings and on yew shrubs in residential landscapes (Curtis and Eshenaur 2022a, 2022b). In their experiments, one spray of Trico in the autumn repelled deer from browsing on Christmas trees through the winter. The one failure for this product was for yew shrubs placed at one residence in Rochester, NY, while shrubs placed at three other residences escaped damage. This experience demonstrates that even excellent deer repellents can fail if deer populations are high enough and/or when deer are starving.

It is well known that fats (consisting of fatty acids) and soaps (salts of fatty acids) can be repellent to deer. A Japanese patent from 2017 (JP3212224U) reveals that lard (pork fat) applied with other disgusting ingredients to absorptive fabric strips or ropes makes an effective deer repellent. A commercial product called Hinder® contains ammonium soaps of fatty acids and has been available since the 1990s.

In Poland, Belarus, Latvia, Scandinavia and Ireland, individuals wrap bits of raw sheep wool around the shoots of plants to protect them from being eaten by deer during the winter. As noted on their website (Kwizda 2024), Kwizda followed this traditional European method, but substituted the body fat of sheep for the wool grease found on raw wool, as the active ingredient for their Trico deer repellent.

At the time I studied pomology at Cornell University, the standard deer repellent being used in orchards at the time was bags containing hair from barbershops tied onto branches of fruit trees. At the time (1981) it was already understood that the repellency of the human hair was dependent on the odor of sebum (hair grease). Orchardists were advised to only use hair from barbershops, as men’s hair isn’t washed before being cut, whereas hair from beauty parlors is washed and so would no longer possess repellent odors.

The closest thing to obtaining the essence of hair is to purchase lanolin, the greasy substance coating sheep wool that must be removed before spinning wool into yarn. Lanolin, as a byproduct of wool processing, is available in large quantities worldwide. It is known to be non-toxic because it has been used as a skin softener, to prevent diaper rash (by “lanolizing” cloth diapers) and even is used by breast-feeding mothers to assist in skin irritation, meaning that it has been safely ingested by infants. It has food-approved uses and can be found in some chewing gum.

Surprisingly, even though there is cultural use of raw sheep wool as a deer repellent in Europe my work appears to be the first effort to formulate lanolin into a sprayable emulsion for use as a deer repellent.

U.S. EPA pesticide regulations allow homeowners and farmers to make and use their own pesticides if all components are on EPA’s list of approved active or inactive ingredients exempt from registration. A subset of these ingredients, which includes lanolin, can even be applied to edible crops.

Other legal considerations for homemade pesticides are that the product must be used on your own property and that it cannot be sold to anyone else. The rest of this article describes two deer repellents: one based on lanolin, and the other based on milk fat. These repellents can be used as do-it-yourself deer repellents.

The lanolin-based repellent is more challenging to make and use, and cleaning spray equipment requires a limonene-based solvent. Its advantage is that it uses hypoallergenic ingredients and so sprays of this to protect fruits and vegetables can be applied until the day of harvest.

The milk fat-based repellent could also be suitable for use on fruits and vegetables, but only for households where no one has milk allergies. The deer repellent using milk fat uses materials available at the grocery store, and the spray equipment is easily cleaned after use.

Emulsions are either fatty materials suspended in droplets within a water-based matrix (called an oil-in-water emulsion, a good example is milk or cream), or a water-in-oil emulsion. Lanolin is known as a good emulsifier for water-in-oil or invert emulsions.

A lanolin-based deer repellent I have designed and tested including sodium lauryl sulfate as an active ingredient will soon be marketed as No-Does and Buck Stop. (Note: sales of these products will return a royalty to the author and the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station). By maintaining a high concentration of lanolin in a concentrate, the commercial product doesn’t separate into liquid and solid layers and can be shipped in small containers.

One drawback is that at low temperatures, this concentrate solidifies, and so must be gently heated to regain a milkshake consistency.

For homeowners interested in making their own repellent using lanolin, target a final concentration of 5% lanolin in a mixture emulsified with either sodium lauryl sulfate (0.3% final concentration) or a commercially available insecticidal soap.

Start with warm water, and use a stirrer designed for mixing paint in 5-gallon buckets, driven by an electric drill, to obtain a uniform, milky emulsion (Fig. 2). Strain the material through a screen into a garden sprayer and apply it as a fine, low volume spray mist to foliage you wish to protect. Be sure not to fully wet the foliage of plants with “blue” foliage (such as blue hostas) caused by cuticular waxes, or else you may turn the foliage green. This doesn’t harm the plant, but it changes their aesthetics.

For the milk fat-based repellent, mix Half & Half (or similar brand) of dairy creamer with an equal volume of water. Milk and cream are a convenient source of animal fats because they are already in a stable emulsion and no other ingredients are needed to make a sprayable mixture. For either deer repellent, about two gallons of mixture per acre are adequate for repelling deer.

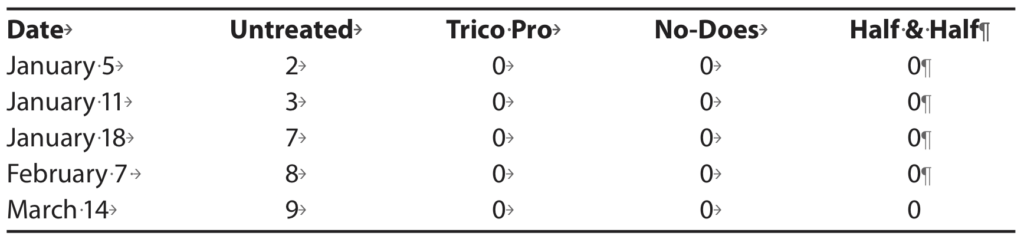

A comparison of all three repellents, along with an untreated control group without deer repellent, took place this past winter at the Valley Laboratory, in Windsor, CT. Small potted yew shrubs were sprayed once with Trico Pro, No-Does, or milk fat-based repellents, using an atomizer to mist the foliage with 5 mL (one teaspoon) of repellent per plant on Dec. 7. Plants were photographed in front of a white background to record their appearance before and after the experiment (Curtis and Eshenaur 2022a, b). Plants were then placed under a power line right of way amongst woods at the Valley Lab property, where deer had been eating forage crops all summer.

Because earlier experiments have demonstrated that these fat-based deterrents can affect deer behavior at about 3-4 meters, pots were spaced 4 meters apart in a square configuration for each replicate. The experiment was a randomized complete block design with nine replicates, and each block was at least 4 meters away from other blocks.

Plants were then observed irregularly through the winter to note when feeding was first observed, with the results as indicated in Table 1 above.

All three of the repellents worked admirably and protected the shrubs at a high level of statistical significance (P < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test) from being browsed by deer. As of the date of writing, there was no browsing on any of the shrubs treated with any of the three deer repellents based upon animal fats, amounting to more than four months of protection with a single application.

Fat-based deer repellents have special value. Based upon the physical properties of fats, it is likely that these materials are absorbed into the cuticular waxes of leaves, where they cannot be removed by rain. This contrasts with soaps, which can be washed off foliage. For example, the Hinder® label recommends reapplication following rain events. The field tests in 2023 were subjected to excessive rainfall, and yet the treatments remained effective under our conditions for more than 12 weeks. These repellents are non-toxic to humans, non-phytotoxic, biodegradable, and take advantage of an apparently large difference in the sense of smell of humans and deer. While we can barely detect the odor of these materials, deer obviously can detect tiny quantities, resulting in prolonged behavioral avoidance of treated plants. We have observed that deer avoid properties broadly treated with the lanolin-based deterrent. Deer appear to avoid treated sites, which may enhance the repellent’s effectiveness. If a herd avoids a treated area for a long enough time, they may no longer recognize a property as being part of their foraging territory, prolonging the effective protection of landscape plantings.

Note that fats or soaps applied to plants that are deterrent to deer can stimulate feeding by voles! Do not allow the spray of fat or soap-based deer repellents to drip down the trunk to “flavor” the trunk near the soil line, as this can lead to trunk girdling by rodents.

Rich Cowles has worked at the Valley Laboratory of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station for almost 30 years. Although his Ph.D. is in entomology, he has also worked on plant diseases, plant improvement, and plant nutrition.

References

• Curtis, P.D. and Eshenaur, B.C. 2022a. Trico: A novel repellent for preventing deer damage to ornamental shrubs. Human-Wildlife Interactions 16(1): 22-28.

• Curtis, P. D. and Eshenaur, B.C. 2022b. Using repellents for reducing deer damage to Christmas trees. Great Lakes Christmas Tree Journal, Winter 2022, pp. 23-28.

• Kwizda, 2024. Europe’s leading deer repellent Trico® receives registration for Canada. https://www.kwizda-agro.com/en/europe-s-leading-deer-repellent-trico-r-receives-registration-for-canada~mpr35763