By Kathy Connolly

Millions of people will flock to national parks this summer, anticipating the oceanside cascades at Acadia, the wildlife at Yellowstone, or the views at Shenandoah. All these worthy destinations delight their visitors at the same time as they preserve extraordinary elements of the natural landscape and provide wildlife habitat.

But, according to some ways of thinking, the national parks are more like nature museums than nature itself.

One of those thinkers is Dr. Douglas Tallamy, whose 40 years of research have aimed to understand how insects interact with plants and how such interactions determine the diversity of animal communities. He is probably familiar to many Connecticut Gardener readers through his books and many talks and webinars. (See sidebar below for a list of Tallamy’s publications.)

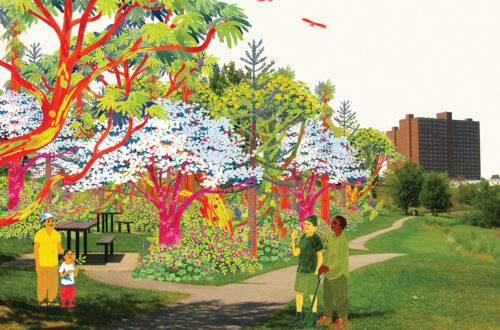

“We cling to the notion that nature should be saved where nature remains, not where humans work, live, farm, or play,” he writes in Nature’s Best Hope, a bestseller (Timber Press, 2020). He exhorts his audience to adopt a different perspective: We cannot continue to exile the natural world to parcels of land where no people reside. Insects, birds, and all wildlife need connectivity, just like people.

Instead of our fragmented landscape, he invites millions of private property owners to voluntarily plant native plants, filling in the national mosaic between the lines. He also calls for neighbors to nix pesticides, turn down outdoor lights, and remove invasive plants.

If you’ve read his books or heard his talks, you already know he has a name for the idea: the Homegrown National Park.

Tallamy calls it the “largest cooperative conservation project ever conceived or attempted.” The goal is to revive habitat for the other orders of life across contiguous spaces everywhere. If many people address the issues with a few simple actions on their home grounds, the solution need not be funded, engineered, or implemented by governments.Tallamy has explained this vision to hundreds of thousands of people. One of those people is his current business partner.

An Unlikely Convert

At the suggestion of a neighbor, Michelle Alfandari went to hear Tallamy speak at a school auditorium in Sharon, Conn, in 2017. She had never heard of him or his ideas. Indeed, Alfandari was an unlikely candidate for a talk on “How Native Plants Sustain Wildlife.” She was a new-to-the-country city girl, easing into semi-retirement. She’d run her own New York City global licensing and marketing agency for 30 years. Her clients included Mack Trucks, Snap-on Tools, The New York Times, Tour de France, National Trust for Historic Preservation, The Victoria & Albert Museum, and the Ritz Hotel Paris.

“I went with an open mind, not knowing what to expect,” she says. “I walked away that day being introduced to biodiversity, loss of habitat, planting native, and understanding that our future quality of life was at risk. The next generations were at risk. I was also shocked by how quickly change needed to happen.”

In other words, she got the message. As time passed, Alfandari reflected on what she had heard. “I felt confident that if people knew how big an impact they could have with so little effort, they would act. Doug’s message was clear to me, someone who was never really focused on conservation or interested in gardening. I felt certain it would move others.”

In 2019, she picked up the phone. Alfandari and Tallamy began a discourse about the mechanics of turning his message of individuals regenerating biodiversity into widespread action. “We both knew that for these ideas to work, they had to reach a bigger audience than ‘the choir,’ the people who were already on board,” she says.

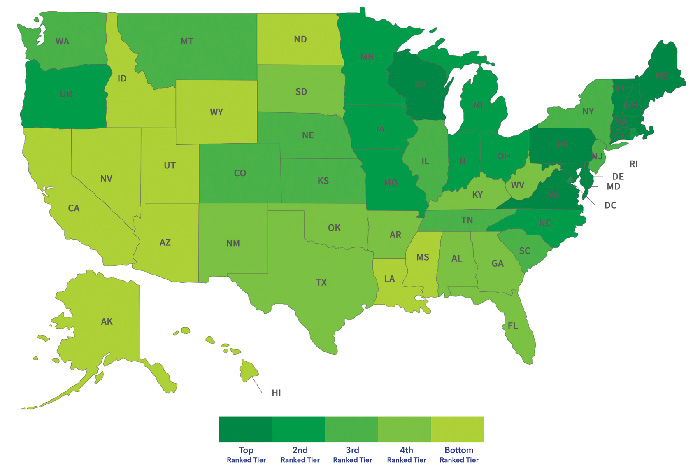

In 2020, they launched an interactive national map. Site visitors could mark their properties or planting goals on the map as “pieces” of the Homegrown National Park in the US and, more recently, Canada. The map aims to demonstrate how many people have heard the message and acted. As of this writing, nearly 27,000 individuals are on the map, representing about 76,000 acres.

The initial goal was 20 million acres out of the more than two billion in the US.

“This goal was based on Doug’s initial focus on homeowners, thus one-half of the green lawns on privately-owned properties,” says Alfandari. “But our focus now is on all private land. We aim to exponentially increase acreage year to year.”

HNP’s 2023 goal for the U.S. is 125,000 acres, and for Canada, 40,000 hectares.

The map is only one element of the website, but an evolving one. “People believe what they can see,” says Alfandari. “The map is a visual demonstration of individual action and each person’s part to the greater whole of others’ participation. It encourages those already on the map and inspires those not yet joined.”

Making it easy to get started is critical to the movement’s success. The website offers a steadily increasing list of resources, including links to native plants by region, ways to buy plants, landscapers, numerous videos, tools for participants and partners, and ‘Tallamy’s Hub.’

“Having spent many years in marketing, I sensed the elements of a classic communications challenge especially considering our demographic is everyone – everywhere,” says Alfandari. “The problem needed leadership and spokespeople like Doug, but it also needed specific calls to action, demonstrations of success, repetitions, and measurements.”

Since that 2020 foray, the team established a nonprofit, started fundraising, formed a board, recruited supporters, and received sponsorships.

Then, in 2022, an anonymous donor offered $450,000 unsolicited. At this writing, HNP is searching for an executive director to grow the movement. (The search will end in early May, supposedly. See the job description at https://bit.ly/3ynWuWW

Collaborations

“We feel certain that HNP is the largest cooperative conservation project ever conceived or attempted, says Alfandari, pausing on the word co-operative. “We’ll continue to keep our unique focus on reaching those unaware of the biodiversity crisis – people like I once was – but we’ll do it while working and collaborating with aligned businesses, nonprofit organizations, and other entities with aligned missions.”

HNP’s online map is one of several among nonprofits in the biodiversity and pollinator category. For instance, Pollinator Pathway’s interactive map documents participation in 300 towns across 11 states and Canada. More than half of Connecticut towns are listed on Pollinator-Pathway.org but HNP is currently the only one that aims to aggregate all mission-aligned groups and individuals.

“We are convenors, amplifiers, and collaborators, not competitors, says Alfandari. “What differentiates HNP is that we capture all initiatives on the HNP Map. It is a way to enhance all like-minded efforts and inspire others to join.” She believes there need to be many groups because there are many audiences, and each audience is reached in nuanced ways.

“Groups with deep local connections are especially important,” she says. “They have history and a track record. Their messages are meaningful to their members and audiences.”

HNP collaborates with several national groups, such as Wild Ones (www.WildOnes.org), where Tallamy is a lifetime honorary director. He also provided the research for native plants with the National Wildlife Federation’s Garden for Wildlife (https://gardenforwildlife.com), an ambitious program that aims to put millions of seed-grown, neonicotinoid-free native plants directly into the hands of people who are planting the nation’s landscapes.

GFW provides ecoregional “keystone” plants essential to insect survival. Plant selections are based on research by Tallamy, his graduate students, and other insect scientists. Customers enter their zip codes to find suggestions.

Both GFW/NWF and HNP have container gardening guides. A recent HNP initiative, “No Yard? No Problem,” was launched last year and is about to be updated. It is a guide and resource for container gardening with native keystone plants by ecoregion.

Reaching Young People

In April 2023, the bestselling book Nature’s Best Hope was republished in a “young reader’s” edition, targeted to ages eight to 12 and grades three to seven. Children’s author Sarah L. Thomson adapted the text.

“Our kids are the future stewards of the planet,” says Tallamy. “If they are afraid of stewarding nature, if they don’t know how to steward nature, if they don’t love stewarding the natural world, they will be lousy stewards.”

What About Non-native Plants?

Tallamy emphasizes native keystone plants, the ones that support the most insect and bird species, but don’t forget feeding specialists that can survive only with the presence of one or two plant species (Think monarchs and milkweed.) To find the names of keystone species in your zip code, visit nwf.org/keystoneplants

A study conducted by Tallamy’s PhD students suggests that yards can maintain a functional food web as long as at least 70% of the plant biomass is native. “There is room for compromise, especially with the herbaceous layer of plantings,” says Tallamy. To find the names of native species in your zip code, visit nwf.org/NativePlantFinder

It’s also important to avoid or remove non-native invasive plants. Common examples include burning bush (Euonymus alata) and barberry (Berberis vulgaris and Berberis thunbergii). Some other common non-natives to avoid include Dame’s rocket, Chinese and Japanese wisteria, vinca, English ivy, Chinese privet, nandina, Russian and autumn olive, most honeysuckles, Bradford pear and other callery pears. These are unproductive for the vast majority of native insects. They also take up space rapidly and make it difficult to add more productive plants. For a list of plants officially considered invasive in Connecticut, consult the Connecticut Invasive Plant Working Group’s website at cipwg.uconn.edu

“We cannot afford any more lousy stewardship,” says Tallamy. Plant native, add your location to the map and spread the word.

Kathy Connolly writes and speaks on horticulture, landscape design, and low-impact land care. Kathy has a master’s degree from the Conway School of Landscape Design. She lives in Old Saybrook. Her website is SpeakingofLandscapes.com

KEYSTONE NATIVE PLANTS

• Quercus (Oak)

• Prunus (Plum)

• Betula (Birch)

• Populus (Cottonwood)

• Acer (Maple)

• Malus (Crabapple)

• Carya (Hickory)

• Pinus (Pine)

• Vaccinium (Blueberry)

• Salix (Willow)

• Solidago (Goldenrod)

• Symphyotrichum (Aster)

• Helianthus (Sunflower)

• Rudbeckia (Black-eyed Susan)

Recent Books by Douglas Tallamy

• Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard, Timber Press, 2020, and Young Readers edition, adapted by Sarah L. Thomson, Timber Press, April 2023.

• The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees, Timber Press, 2021

• The Living Landscape: Designing for Beauty and Biodiversity in the Home Garden by Rick Darke and Douglas W. Tallamy, Timber Press, 2016

• Bringing Nature Home: How Native Plants Sustain Wildlife in Our Gardens, Timber Press, 2009

2 Comments

Lauren Gorham

Fantastic article Kathy, thank you! I will work to put my yard on the map. 😊

Kathleen Connolly

Thanks, Lauren! It’s a great goal–and easier to reach than most of us think. Have a great growing season. Kathy