By Will Rowlands

We’re hearing a lot these days about “native shaming” and even “cultivar shaming.” It’s even become a meme. People are getting grief if they plant anything other than natives. Some are even catching flak if they use anything besides “straight-species,” “true native” or “wild type” plants in their gardens. It’s gotten to the point where growers are wary of using the term cultivar or nativar.

Just to be clear, we are proponents of native plants, organic gardening and biodiversity and have been since we took over the magazine in 2010. We are also opposed to the use of invasive or genetically engineered plants.

Even so, we find this trend disconcerting. We don’t want to see a horticultural version of the Spanish Inquisition.

What Exactly Is A Native Anyway?

There are differences of opinion. Generalists might say it’s just a plant from our region that was already here when European settlers arrived. (Or, as Emma Marris puts it … “When the white guys got off the boat.”) Of course that differs from place to place and we are now learning that in many locations indigenous people were already practicing landscape management when the first colonists arrived.

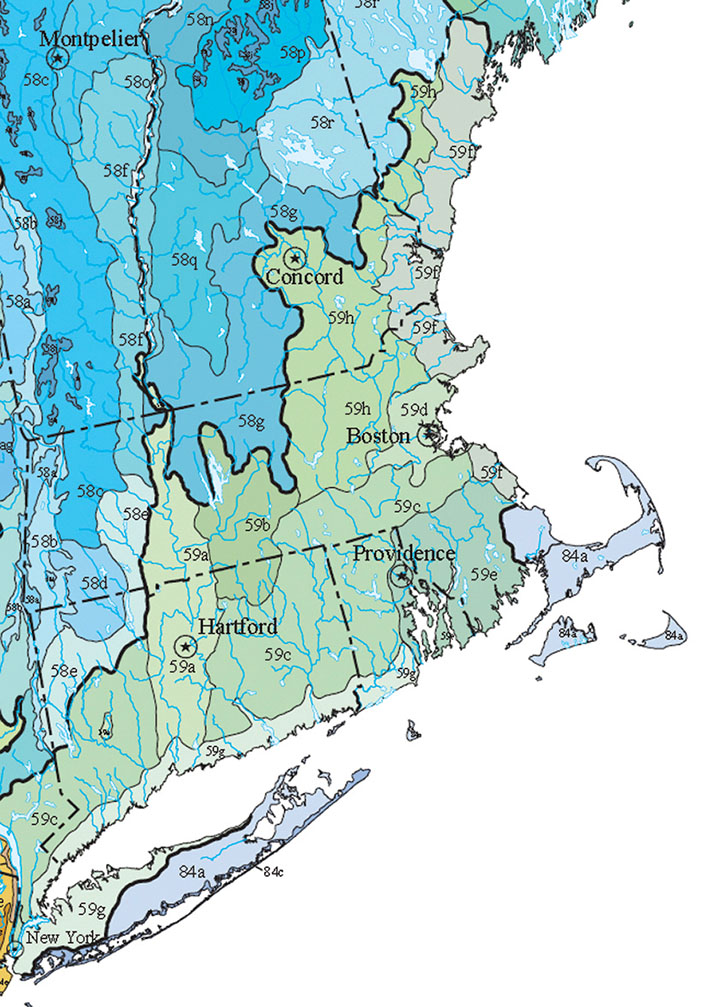

A narrower definition might say it’s a plant indigenous to an Ecoregion. Here’s where it gets complicated. The EPA has divided the U.S. into 15 broad Level I ecoregions, 50 Level II ecoregions, 182 Level III ecoregions and even more Level IV ecoregions. Connecticut itself is composed of seven Level IV subdivisions: Ecoregions 58a, 58d, 58e, 59a, 59b, 59c and 59g. (See map below.)

One could also just say it’s a genotype from our latitude. So where do we draw the line? As local as possible, I guess, but that’s a problem because of the limited availability of locally sourced plants. I’m sure I’d get strange looks if I walked into a nursery and asked for plants from Ecoregion 59g (Long Island Sound Coastal Lowland).

In a recent post on Garden Rant (gardenrant.com) Joseph Tychonievich says there really is no such thing as a straight-species or wild-type native. He argues that all plants have been selected in one way or another and opines … “So we need more ‘nativars’ in the world. More names. More background on how and where and why a plant was selected. And we need to stop pretending that a plant without a cultivar name attached is anything other than a plant about which we don’t have very much information.”

Should We Plant Cultivars?

Donald J. Leopold has this to say on the subject in his book, Native Plants of the Northeast – A Guide for Gardening & Conservation (Timber Press, 2005):

“Should cultivars be planted? It depends on a person’s objectives. If conserving native gene pools is the single most important reason for planting these species, then one should collect seeds from specimens throughout a species’ range of interest (county, state, region) and grow a genetically diverse mix of each species. If one primarily wants to derive the many benefits of native plants (preserving natural heritage, having plants succeed on a difficult site, attracting a diversity of insects), then a cultivar selected from the natural variation within a plant species seems appropriate.”

I found this explanation from Jessica Lubell-Brand (a professor of Horticulture at UConn) in Nursery Management: “It can be rather difficult to define what a native plant is and many definitions exist. Perhaps one accurate definition would identify native plants as those that have evolved and adapted to a specific location (naturally occurring) and have remained genetically unaltered by humans. Often though, plants are described as being native to a country, or native to a large geographic region or native to a state. This is where difficulties can arise.”

Here are four examples of named plants that were collected from nature. We think of them as natives.

Phlox paniculata ‘Jeana’

Phlox paniculata ‘Jeana’ was originally collected by Jeana Prewitt along a river near Nashville, Tenn. It has become famous for outperforming all of the other types of phlox in a recent Mt. Cuba trial.

Is Phlox paniculata ‘Jeana’ a native plant? As far as we’re concerned it is. Not only that, it’s one of the best plants for pollinators, native or otherwise.

Phlox paniculata ‘Jeana’

Ilex glabra Forever Emerald™

In our March/April issue we featured a story by Michael Dirr on Ilex glabra Forever Emerald.™ Inkberry occurs naturally along the entire eastern seaboard. This inkberry was propagated from cuttings collected in the wild in Nova Scotia by Jack Anderson from the Arnold Arboretum. It was originally named Ilex glabra ‘Peggy’s Cove.’ Anderson chose to collect it because it was compact and, unlike most inkberries, has good legs. Nothing unnatural going on there.

Is Ilex glabra ‘Peggy’s Cove’ a native plant? We think so. Not only that, it’s a potential native replacement for boxwoods in the landscape, something we desperately need.

Ilex glabra ‘Forever Emerald’

Cercis canadensis ‘Arnold Banner’

In our July/August 2024 issue, you’ll find a piece on Cercis canadensis ‘Arnold Banner.’ This plant was propagated from a sport discovered on a tree in the Arnold Arboretum’s collection in Boston. It’s a spontaneous, natural mutation of a native plant (Eastern redbud). Nothing phony here, just nature doing its thing.

Is Cercis canadensis ‘Arnold Banner’ a native plant? We think so. It’s nature’s creation. It just happens to be desirable to humans because its flowers are white and have beautiful magenta nectar guides.

Like a lighted runway, the nectar guides lead bees to the nectar.

Hydrangea arborescens ‘Haas’ Halo’

This plant was collected by Frederick Ray from the Pennsylvania garden of Joan Haas. Here’s what Mt. Cuba has to say about it: “Style meets substance. Hydrangea arborescens ‘Haas’ Halo’ is a knockout that offers the perfect combination of horticultural excellence and pollinator value.”

Hydrangea arborescens ‘Haas’ Halo’

•

And, as we learned from Annie White’s work, the only way to really learn about a plant’s usefulness to wildlife is by direct observation. Cultivars of native plants aren’t always bad. We are short on data in that regard so, at least for the time being, the more natives we have to choose from the better.

In general, White recommends choosing nativars that are as close as possible to the original plant. That’s excellent advice because nativars that include a change to reddish, burgundy, purple or blue leaves makes them less valuable as a food source due to increased levels of anthocyanins.

So, not every named native plant was ginned up in a lab by a mad scientist using genetic engineering. Some are just naturally occurring variations of native plants.

It would be easier if the plant names just used variety … say Phlox paniculata var. Jeana. Botanically, a “variety” is a naturally occurring form of a plant population within a species.

It would be great if the full provenance of a plant was given on its tag but some of them are patented and growers can be reluctant to reveal everything.

Let’s create a big inclusive tent and make it easy to get in. Plant more natives, learn as you go and have fun doing it.

Doug Tallamy recommends planting at least 70% natives if you’re interested in creating viable wildlife habitat. Check out homegrownnationalpark.org for more information.

Edwina von Gal’s 2/3 for the Birds – 234birds.org – is another good approach. Whenever you buy plants, make sure at least two-thirds of them are natives.

Our friend Nancy DuBrule-Clemente puts out a regular email blast. After talking about natives and vegetables she ends with a section called “The Other 30 Percent.” Following Tallamy’s guideline, this is where we get to play and plant whatever we want (as long as it’s not invasive).

“What we do know is that nativars are, in many cases, a good alternative to a wild plant species and can provide excellent ecosystem services to the landscape. People should feel empowered to experiment with nativars in their gardens, and to request information about plant provenance at garden centers,” says Jeff Downing, Mt. Cuba Center’s executive director.

Knowledge is key. It’s always important to know the origin story of your plants. It’s also wise to use genotypes from our region of the country. Don’t be afraid to ask questions and don’t be afraid to make mistakes.

Doug Tallamy in one of his “Tallamy Tidbits” (available via the Aspetuck Land Trust at aspetucklandtrust.org/doug-tallamy-tidbits) talks about buying some native beech trees on sale in New Jersey only to see them leaf out too early at his Delaware home. He hypothesizes that they originally came from the Carolinas.

If we can agree that planting natives is a good thing, we should be able to agree that having more native plants to choose from is also a good thing. A lack of straight-species natives and locally sourced ecotypes at nurseries and garden centers is part of the problem.

“It is not the addition of introduced plants to our landscapes that destroys biodiversity; it is the removal of the native plants upon which that biodiversity depends. Landscapes with a healthy dose of keystone plant genera almost always have room for some striking non-invasive introduced ornamentals without losing their ecological clout,” says Tallamy.

By all means, go 100% straight-species if you’re so inclined, but getting confrontational about the whole thing might have a negative impact on the native plant movement. If you’re really gung ho and want to grow your native plants from seed, check out the Wild Seed Project (wildseedproject.net). They have new book out … Planting for Climate Resilience in Northeast Landscapes.

The reality is that not everyone is ready to jump in with both feet and become a native plant purist and we don’t want to alienate people. Let’s be inclusive. Let’s not let perfect be the enemy of good, and anybody planting a native plant is doing a good thing. It’s even possible that cultivars and nativars will act as gateway plants on the way to straight species. After all, you have to start somewhere.

“I would love to see straight species sold right alongside their cultivars so that people who value function over aesthetics have the option to buy these plants,” says Doug Tallamy.

We agree. Just remember … gardeners who plant cultivars of native plants or nativars aren’t the enemy.

It seems to me that the extensive incursions of invasive plants present a much greater threat to biodiversity than home gardeners planting some nativars. According to the U.S. Forest Service, invasive plants cover 133 million acres nationwide and about 1.7 million acres are infested annually.

If you’re really concerned about biodiversity, consider getting involved with the CT Invasive Plant Working Group (CIPWG). You can join their listserv at cipwg.uconn.edu and learn about events, workshops and volunteer opportunities. Their website is also a great source of information on invasive plants.

So what’s the bottom line? If you’re involved with conservation areas and ecological restoration projects (or live near one) the conventional wisdom says you should use straight-species native plants.

If you’re a home gardener, you should remove any invasive plants (if you haven’t already) and start using more natives. Whether you progress from planting cultivars and nativars to straight-species natives and growing native plants from seed will be determined by your level of interest and commitment.

Plant parentage matters. Don’t be afraid to ask about locally sourced natives at your garden center or nursery. Things will change if enough of us ask.

SOURCING NATIVE PLANTS

For more information on sourcing native plants check out

https://www.sourcingnativeplants.com

Their team, which includes Doug Tallamy, is composed of scientists and professionals with a variety of backgrounds. They include geneticists, ecologists, public garden professionals and more.

Their basic credo: 1. Nativars can play an important role in sustaining the local food web. 2. Not all nativars are equal in their ability to support food webs. 3. Genetic backgrounds of native plants can inform their suitability.

Questions You Can Ask When Shopping for Native Plants

• Where was this plant grown?

• Where does the nursery stock for this plant come from?

• Is this plant grown from seed?

• Is this plant a hybrid?

• Is this plant a selection of a naturally occurring wild species?

• How does the foliage color of this plant differ from the wild species?

• How does the flower size, shape and color differ from the wild species?

• Has this plant been bred for disease resistance?

• Is this plant a dwarf version of the wild species?

• Is there research available on this plant’s ability to support wildlife and provide other ecosystem services?

What’s In A Name?

• Straight species – a plant species that has not been bred or modified.

• Ecotype – a plant adapted to grow in a specific ecological region.

• Cultivar – A cultivated variety. Many are created by human manipulation but some originate from wild plants that have unique characteristics.

• Nativar – A cultivar developed from a native plant.

• Variety – A naturally occurring variation of a plant within a species. Most varieties will produce seeds that are true to type.